Key Provisions and Operational Mechanisms

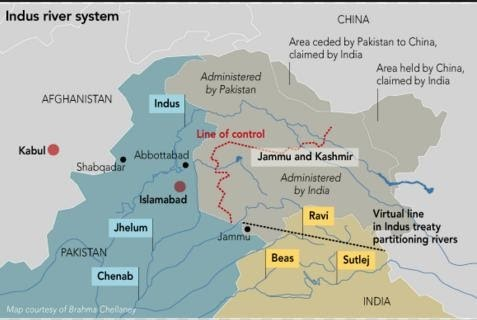

The treaty outlined specific rights and obligations for both India and Pakistan. India was given full control over the eastern rivers for consumptive and non-consumptive use. However, while India was allowed non-consumptive use (e.g., for hydropower generation) on the western rivers, it had to ensure that it did not adversely affect the volume or flow available to Pakistan. To this end, the treaty included a rigorous notification process for new Indian projects on western rivers.

Mechanisms for conflict resolution were also embedded in the treaty. In the case of a dispute, the PIC would first attempt bilateral resolution. Failing that, a Neutral Expert appointed by the World Bank would mediate. If the issue escalated further, it could be taken to a Court of Arbitration.

Why the Treaty Has Endured

Despite enduring three full-scale wars, multiple border skirmishes, and decades of mutual distrust, the IWT has stood firm. Its resilience can be attributed to the technical specificity of its terms, the ongoing role of the PIC, and the World Bank's indirect oversight. Moreover, both nations have historically recognized the strategic utility of water cooperation as a stabilizing force.

The Pahalgam Attack and the Suspension of the Treaty

The terrorist attack in Pahalgam, allegedly orchestrated by Pakistan-based groups, has been described as the worst atrocity against civilians in India since the 2008 Mumbai attacks. It led to an outpouring of public anger and demands for decisive government action. In a rare and dramatic move, the Indian government suspended its implementation of the IWT, signaling a fundamental reassessment of its obligations towards a State it accuses of fostering terrorism.

India’s Ministry of External Affairs issued a statement that while it continues to respect international obligations, it cannot be expected to cooperate on water-sharing while Pakistan allegedly continues to harbor anti-India militant groups. It also declared the military attachés in the Pakistani High Commission persona non grata, a diplomatic signal underscoring the severity of India's response.

This action is grounded in a broader context of State-sponsored terrorism that has cost India thousands of lives over the last three decades. From the insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir to high-profile attacks like those in Mumbai (2008), Pathankot (2016), Uri (2016), and Pulwama (2019), a consistent pattern has emerged—where India has provided evidence of Pakistani complicity or support to terrorist groups. Such sustained State sponsorship of terrorism constitutes, in India's view, a material breach of good faith and international norms, undermining the very basis of cooperative frameworks like the IWT.

Implications for Pakistan

The IWT is critical to Pakistan, as nearly 80% of its agricultural output depends on irrigation sourced from the Indus basin. A disruption in the flow of the western rivers could precipitate severe water scarcity, food insecurity, and economic instability. Moreover, the specter of Indian upstream infrastructure projects — including the Kishanganga and Ratle dams — now looms larger, with fears that India might unilaterally alter water flows in times of tension.

In legal terms, Pakistan could take the matter to international forums, including the International Court of Justice (ICJ), though the IWT restricts the jurisdiction of such courts unless both parties agree. The World Bank, though not an adjudicator, may be called upon to mediate anew.

Potential for Regional Escalation

The suspension of the IWT increases the risk of escalation in a region already fraught with nuclear tensions. Water scarcity is a known conflict multiplier, and in South Asia, where both India and Pakistan rely heavily on shared water resources, it is a flashpoint that could lead to broader military confrontation. A prolonged abeyance or formal abrogation of the treaty could also impact Afghanistan, which is negotiating its own water-sharing agreements with Pakistan.

China, an upstream riparian in the Brahmaputra basin and an ally of Pakistan, may also enter the fray, complicating the hydropolitical landscape. With climate change exacerbating glacial melt and altering monsoon patterns, the urgency of regional water governance has never been greater.

Environmental and Humanitarian Concerns

Beyond geopolitics, the suspension of the IWT may have devastating environmental consequences. Uncoordinated water management could lead to over-extraction, mismanagement of flood control, and ecological degradation. The people of both nations, especially those living in the arid regions of Sindh and Punjab in Pakistan, and Jammu and Kashmir in India, stand to lose the most from disrupted water flows.

Civil society groups, environmentalists, and humanitarian organizations have urged both governments to delink water cooperation from political tensions, citing the treaty's primary objective: to ensure equitable and peaceful use of transboundary water resources.

International Legal Perspective

From a legal standpoint, India's suspension of the IWT is not equivalent to withdrawal. International treaty law, including the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969), allows for suspension of treaty obligations in response to a material breach. India could argue that Pakistan's support for terrorism constitutes such a breach.

However, the threshold for suspension is high, and any unilateral move risks eroding India’s image as a responsible international actor. While the IWT itself contains no explicit exit clause, its continued observance is vital for maintaining the sanctity of international legal norms.

Conclusion: The Road Ahead

India's suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty is a watershed moment in South Asian diplomacy. It reflects the changing contours of India’s strategic thinking, where soft power and strategic restraint are now being recalibrated in the face of persistent asymmetric threats. While the move may yield short-term diplomatic and psychological leverage, the long-term costs—environmental, humanitarian, and geopolitical—must be carefully weighed.

Given Pakistan's long-standing support to cross-border terrorism, India's action is also a moral and strategic assertion of its sovereign right to defend its citizens. The global community must recognize that peace is not possible in an environment where one side bleeds while the other shields the perpetrators.